By Kylie Marsh

Kylie.marsh@triangletribune.com

DURHAM – The Carolina Theater was packed on Martin Luther King Jr. Day, its seats filled with people of all races.

But it took a battle, sometimes violent and life-threatening, led by Durham’s determined and revolutionary youth to get to this point. Although the theater was owned by the city of Durham in 1926, it was not fully integrated until 1963.

Monday evening’s event was the premiere of filmmaker JD James’ documentary “Breaking the Booth,” which told the story of nonviolent protests, guided by Attorney Floyd McKissick Sr., to integrate the city-owned theater.

Audience members were not just onlookers. They included local notables, including some of the original protesters. The significance of the King Holiday and the current political climate was not lost on audience members or the Carolina Theater team.

Right before the documentary, Chapel Hill Poet Laureate Donovan Livingston recited a poem highlighting King’s staunch support of adequate living conditions; a sustainable, livable income; and a sound, quality education; things which are still fiercely fought for today.

Audience members were sitting in the very seats that were shown in the film’s title screen. The documentary showed that the building was specifically designed, with separate ticket windows and entrances, to be segregated. Before integration, Black patrons had to climb a narrow, un-air-conditioned staircase of 97 steps to reach the upper balcony with lower visibility. The balcony was negatively dubbed “the buzzard’s nest.”

In the documentary, protester Vivian McCoy said the theater “belonged to the people of the city,” which is why it was only right that it be fully integrated.

Students held constant picket lines outside of the theater and were under pressure to maintain strict stoicism in the face of jeers and violence from white onlookers. “We didn’t just turn the other cheek,” said Walter Riley, who was president of the North Carolina’s NAACP Youth Chapter. “We were nonviolent because we knew that was the method that would father the masses of people.”

The theater was owned by the city but leased to private owner Charles Abercrombie, who feared that white patrons would stop attending if fully integrated. Durham Mayor Wense Grabarek met with Black constituents at the former building of Saint Joseph’s African Methodist Episcopal Church. He faced criticism by assembling an 11-person committee with the promise of moving forward negotiations, though nine of the 11 members were white.

When all Durham businesses voted to integrate, except the Carolina Theater, Black schoolteacher Bessie McLaurin dared to sit in the main theater among white patrons, proving that there was no uproar. Abercrombie’s fears were unfounded, and Black patrons were finally allowed to sit wherever they pleased.

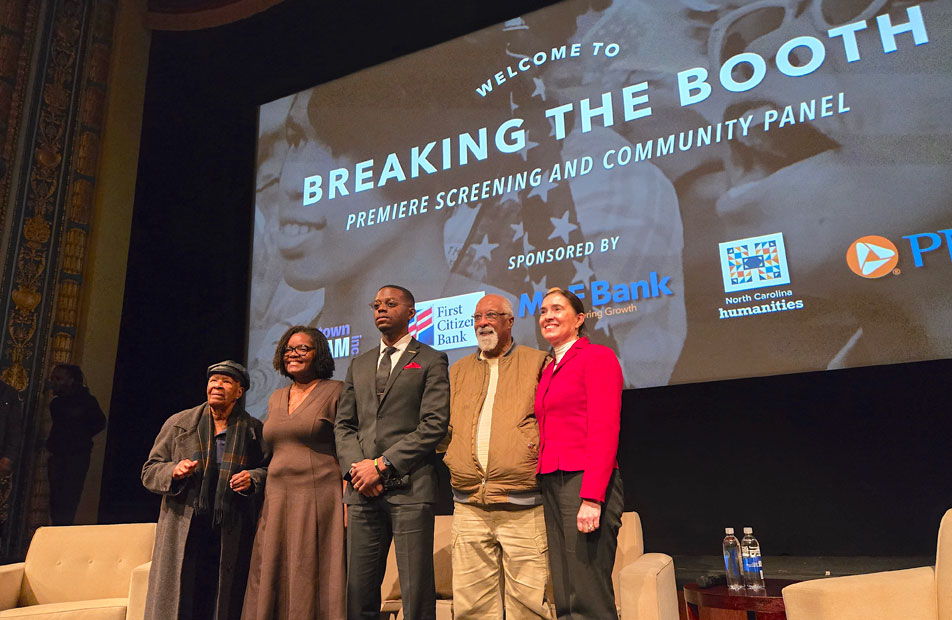

Following the film screening, a panel discussion connected the significance of the past struggles for integration, civil rights and social justice on today’s climate, as well as hope for the future. Panelists included Vivian McCoy, N.C. Central law professor Irving Joyner, Carolina K-12 Director Cori Greer-Banks, N.C. Supreme Court Justice Anita Earls and Durham Public Schools 2025 Teacher of the Year, Alec Virgil.

Panelists discussed the role of the youth, the role of educators and the ambiguity of the law in moving the struggle for integration forward.

McCoy said, as a child, she and her peers who were out protesting were not fully aware of the risk to their lives. She reminded audience members that the Bull City was “heavily infiltrated” by the Ku Klux Klan, but also connected those times to today.

“What we’re suffering from is basically racism. (But) Don’t think that other Black people liked what we were doing,” McCoy added, saying that people, at times, believed McKissick Sr. to be “too militant.”

Virgil said young people today need to be listened to most of all, rather than “preached to.”

“We need to encourage young people to have their own ideas,” he said. “Many older folks don’t give an opportunity for young people to say what they think.”

Virgil said the students want to see “that they count and that they matter.” He mentioned how some of his students organized the major student walkout in early November in response to Immigration and Customs Enforcement’s presence in Durham.

Joyner also reminded audience members that Durham was considered progressive at the time, himself coming from La Grange, a small town in Eastern N.C. However, the city council and the mayor did not move on the issue of segregation, and it was the youth that had to stand up and fight for what was right.